Suicide

Someone close to you has died. Your grief is intensified because the death was a suicide. The healing process will be painful and often seem unnaturally slow. Understanding your emotions, as well as learning something about suicide in general, may ease your grief.

WHY SUICIDE?

Suicide cuts across all sex, age, and economic barriers. People of all ages complete suicide, men and women as well as young children, the rich as well as the poor. No one is immune to this tragedy.

Why would anyone willingly hasten or cause his or her own death? Mental health professionals who have been searching for years for an answer to that question generally agree that people who took their own lives felt trapped by what they saw as a hopeless situation. Whatever the reality, whatever the emotional support provided, they felt isolated and cut off from life, friendships, etc. Even if no physical illness was present suicide victims felt intense pain, anguish, and hopelessness. John Newer, author of After Suicide, says, “He or she probably wasn’t choosing death as much as choosing to end this unbearable pain.”

Were there financial burdens that couldn’t be met? …marriage or family problems? …divorce? …scholastic goals that weren’t achieved? …loss of a special friendship? …the death of a close friend or spouse? A combination of these or other circumstances could have precipitated suicide, or it could have been a response to a physiological depression. Although many people face similar problems and overcome them, your loved one could find no solution other than death.

But sometimes there are no apparent causes. No matter how long and hard you search for a reason, you won’t be able to answer the “WHY” that haunts you. Each suicide is individual, regardless of the generalisations about the “whys”, and there may be no way you will completely understand the suicide victim’s thought process.

As you look for answers and understanding, you also need to deal with your feelings of shock, anger and guilt. The intensity of your feelings will depend on how close you were to the deceased and the degree of involvement you had with his or her life. As each suicide is individual, so will your reaction, healing, and coping process be unique. The general observations that follow may help you deal with your grief.

INITIAL SHOCK – THIS ISN’T HAPPENING!

Shock is a first reaction to death. You may feel numb for a while, perhaps unable to follow a normal daily routine. This shock can be healthy, protecting you from the initial pain of the loss, and it may help you get through funeral arrangements and services. It may last a few days or go on for several weeks. Take some time to be alone, if that’s what you want, but it is also important to be with other people and to return to your normal routine.

After the initial shock you may feel angry, guilty, and of course, sad. These feelings may overwhelm you all at once, and immediately, or they may surface in the weeks, months, and years ahead. You may handle them well initially only to have them return for no apparent reason. These feelings, and the helplessness that comes with them, will pass. Try to understand and accept the things you feel. It is OK, it is healthy, and it is all part of the healing and coping process.

ANGER – WHY AM I SO ANGRY?

As a relative or loved one coping with a suicide death, you may experience anger, often directed at the deceased – “How could he do this to me?” If the deceased was receiving psychiatric or medical care you may ask, “Why didn’t THEY prevent it? You may find yourself angry with God for “allowing this to happen”. The anger may be self-directed – “What could I have done?” or “Why wasn’t I there?”

Don’t try to deny or hide this anger. It is a natural consequence of the hurt and rejection you feel. If you deny your anger, it will eventually come out in other, possibly more destructive ways and it will prolong the healing process. You need to find someone you can talk to about this feeling – perhaps a close friend or your clergyman. You may need to release your anger physically; take long brisk walks or any exercise that is reasonable for your physical capabilities.

Your anger with the deceased is normal when the manner of death is suicide. The deceased has thrown your emotions into turmoil, and caused pain for you and for others you care about.

Anger with the medical or mental health profession can occur if the suicide victim was receiving treatment or therapy. Though you may have had experience with someone unable to help, the professionals are dedicated and well trained, providing help for many people. These professionals will be the first to recognise that your anger is a valid emotion.

If you’re angry with God, share your feelings with a sympathetic clergyman even if you don’t have any close religious ties. Hewett says, “If you’re ticked off at the Almighty, for His sake, tell Him. God is the only one prepared to handle all your anger.”

Don’t deny your anger. Talk about it, think about it, and constructively deal with it.

GUILT – IF ONLY I’D DONE SOMETHING MORE

Perhaps the most intense anger you experience will be the way you feel about yourself. This anger is closely linked with feelings of guilt. “But I just talked with him!” “Why didn’t I listen?” “If only… I should have…” etc. You’ll think of a lot of others.

If the deceased was someone with whom you had regular close contact, your guilt possibly will be intense. And if the death came as a complete surprise, you will be desperately searching for reasons. A person who completes suicide has usually given out some clues, and as you look back on the last few months (or years) maybe you can now see some hints you missed earlier. You’ll wish you’d recognised the problem early enough to do something about it.

Perhaps you were aware of the deceased’s suicidal feelings and you did try to help. You may have thought you had because in the time proceeding the death you noticed he or she seemed to be feeling a lot better and you relaxed your concern. You need to know it’s not uncommon for a suicidal person to feel better once the decision to die has been made. The problem has not been resolved, but the victim has found an answer – suicide.

As you are trying to cope with your guilt feelings, try not to criticise yourself too harshly for your behaviour toward the victim while he was alive. Are you now wishing you could have found the right solutions or offered more support? Thoughts like “I shouldn’t have gone to the movie”, or “I should have been there”, may constantly be running through your head. If you had stayed home, or if you had been with him, the suicide could and possibly would have happened at another time. If you feel your presence at a particular time could have prevented the suicide, you are assuming too much. Of course we all like to think we can help our troubled friends and families, and we do try. But, the person determined to complete suicide is likely to accomplish it.

If you realistically feel there was something you could have done, face it, think about it, and accept it. Your loved one can’t be helped any more, and you need to go on with your life. You can learn from, and grow with, your experience.

Some people believe an individual has a right to end his life. The term ‘rational suicide’ is used to describe a suicide that has been thought about, and planned, perhaps as a way of dealing with a painful terminal illness. This is an area of controversy, and whether you accept it or not, what you do need to think about is that the suicide was an individual decision – rational or not. It was his choice, not yours. You may accept this intellectually long before your emotions accept it.

What value does your anger or guilt have in the healing process and beyond? Rather than letting the hurt isolate you, share your time and understanding with someone else who is hurting. You can provide friendship and support. Get involved with others; actively support suicide prevention services in your area, or any worthwhile cause or issue that means something to you

RELIEF – I’M ALMOST GLAD IT’S OVER

If you were closely involved with the deceased, perhaps his pain and suffering had become an emotional drain for you. You may have felt unfairly burdened, or just exhausted from being involved with an intense situation. Now you may be feeling a sense of relief that you don’t have to worry any more, or perhaps relief that the deceased’s pain has finally ended. A sense of relief when a difficult situation ends is normal. When the ‘end’ is an unhappy one, the relief can still be there, but now it is coloured with guilt. Remember, don’t expect perfection of yourself, accept your relief and don’t let it grow to inappropriate guilt. The late psychiatrist, Dr. Theodore Reik, said, “One can feel sorry for something without feeling guilty”. Remember, too, that the suicide victim saw death as the only relief possible at that particular time.

STIGMA – WHAT DO I TELL PEOPLE?

The stigma or shame, you may think others associate with suicide, stems in part from its historical and religious interpretations. Early Roman and English laws established suicide as a crime because it was thought a person ended his life to avoid paying taxes! Though the Bible itself contains no prohibition against suicide, the early Christian church equated suicide with murder. Today very few laws exist that equate suicide with crime, and those few are rarely invoked.

If your friends seem uncomfortable talking about the death, or even being with you, it’s most likely the type of discomfort felt when facing death of any kind, or a reaction to your discomfort. And if you’re not comfortable relating the circumstances to others, don’t. Your close friends will already know. Let others simply respond to the death of your loved one. You don’t need to share the complete story with those not close to you any more than you would share all the details of a recent surgery with them.

However, it is very important that you do confront the word ‘suicide’. Practice thinking, hearing, and saying it. Don’t try to do this alone. You need someone, or several people, with whom you can share your feelings. For a few days – possibly a week or two – you may want to isolate yourself and take time to recover by yourself. But don’t cut yourself off for too long. Let friends and relatives help you. No one will have any magic answers for you. No one will be able to make you hurt less. But the healing and coping process requires that you talk about your feelings – about all the sadness, anger, hurt and guilt you are carrying around inside you. Friends may provide all the emotional support you need or you may want to join a mutual support group and meet with others who have experienced the suicide of a loved one. The suicide hotline in your area may be able to offer you some understanding and support over the telephone. Often these hotlines are answered 24 hours a day by people especially trained to help you through the rough spots. They will understand your feelings and help you find ways to work things out.

f you need some professional counselling, your doctor, clergyman, or your Mental Health Association can help you find appropriate services. Remember, you may be blaming yourself in some way but here are people who will share your sorrow and help you see things more clearly.

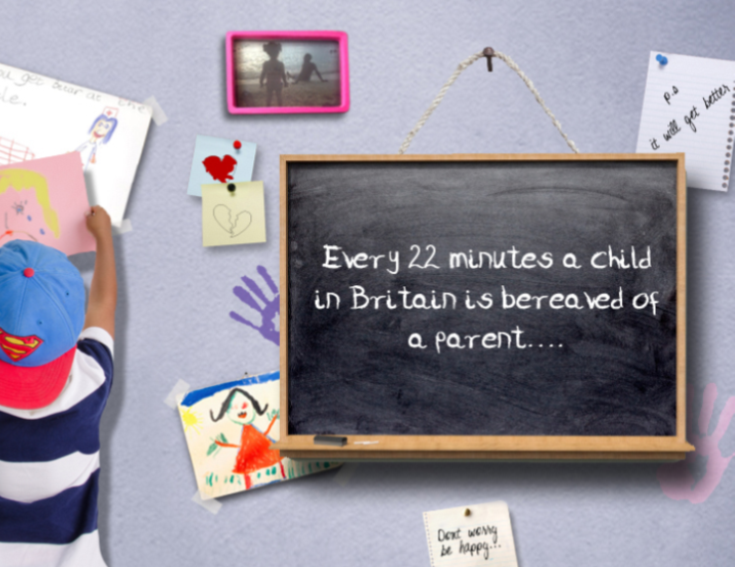

TALKING TO CHILDREN

If the deceased was a parent, or if there are children who were close to the deceased, talking to the children about the death may be one of the most difficult tasks you face. You can’t ignore their needs, especially if you are the primary adult in their lives.

The National Institute for Mental Health says, “By talking to our children about death, we may discover what they know and do not know – if they have misconceptions, fears, or worries. We can help them by providing needed information, comfort, and understanding. Talk does not solve all problems, but without talk we are even more limited in our ability to help.”

Even very young children will be aware of the death of someone in their lives, and they need an opportunity to ask questions and to get truthful answers. If you’re reluctant to talk about suicide – what it means and why it happened – remember that the children are likely to hear about it from other sources, and their confusion will be intensified if they have not had some communication with you. You will need to let them know that the suicide victim was unhappy without giving the impression that death is the answer to unhappiness. You will need to let them know that the deceased felt he had a lot of problems or was ill, without giving them the slightest reason to suspect that they were the cause of the problems or responsible for the illness. They need assurance that YOU will be with them for a long time and that your unhappiness over the death will not be reason for your death.

Older children may be more aware of the circumstances surrounding the death but may be less open about sharing their feelings. They may also feel more responsible than young children and search harder for answers. They may be freer to blame someone, you, for instance.

All children may need some time – a few days at most – to think about the death, to probe their feelings, and to formulate their own questions. The young child’s natural openness may make it easier for him to talk about the death. An older child’s growing sense of maturity may prevent him from sharing feelings.

Some children, regardless of age, won’t ask questions at all and you need to encourage communication. As comfortable as it may be for you to ‘let it ride’, don’t do it. Children, like adults, need to talk about and share their feelings about the suicide. Their reactions may be similar to yours. They may seem insensitive or they may show more anger, hurt, and guilt. You need to accept their reactions, whatever they are, even if you don’t fully understand them.

If communication with a child is difficult, make it a point to talk with people the child has contact with, especially teachers. Teachers need to know what the child is reacting to and they could help you pinpoint emotional responses that may be emerging, such as a change in behaviour at school. They can help you reach the child and provide additional support.

Whether your children are preschool or teen, be honest and listen to what they say as well as to what they do. Make time to be with them. Accept their feelings and share your own. When they ask questions you don’t have answers for, don’t ignore those questions or make up answers. Especially when the death is a suicide, a lot of ‘answers’ will be “I don’t understand either”.

Just as you need emotional, non-judgemental support from someone close to you, your children need your support at this time.

Your library or the local book store may be able to recommend some reading material that will help you discuss death with your children, or books to read to them.

SUICIDE IS NOT INHERITED

Suicide may occur more than once within a family, but it not something that is inherited. In a family, or even among friends, suicide may establish a destructive model or a behaviour to imitate. Thoughts of your own suicide are not an uncommon reaction to the suicide of someone you love and may surface immediately, or years later. A fleeting thought now and then shouldn’t cause alarm. But extended depression and continuing suicidal thoughts need immediate attention. Don’t hesitate to seek out professional help if your problems seem more than you can handle alone.

LOOKING AHEAD

Your grief and sadness will eventually subside, and you will be able to pick up the pieces of your life and rebuild.

There will be times, however, when these feelings will surface very strongly. Holidays or other special times, may renew your sadness. Especially for the first year, you’ll need to decide if you want to maintain traditions you shared with the deceased or if you want new settings and activities to ease painful memories.

On the anniversary of the death, you may want to be alone, attend church, or observe the day in a manner that means something special to you. You may prefer to spend that time with someone close to you or make plans for a family gathering. You can’t avoid these periods of sadness, but whenever possible, try to plan ahead so that they won’t be overwhelming. And sometimes, your loneliness and sadness may come back for no special reason. Be prepared to face this also. Ask for help from friends or a counselling service, if you need it. You can’t expect to forget, but you will be able to cope.

Contact Us

Help is here

Whether you have a question, need a word of encouragement, an idea, or you just want a helping hand, we'd love to hear from you!